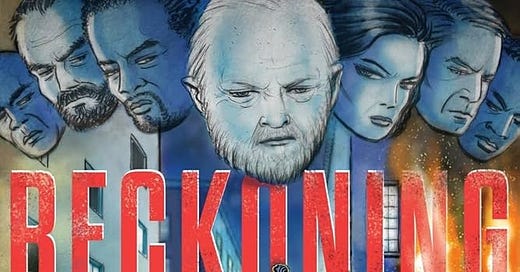

Review of Reckoning: Race War Comes to America by Andrew Bernstein

Over the course of the past decades, Dr. Andrew Bernstein has published a wealth of nonfiction material on topics ranging from politics, economics, and rights to climate change, heroism, and the American education system. In addition, to illustrate the importance of heroism, Bernstein also wrote two novels, Heart of a Pagan: The Story of Swoop and A Dearth of Eagles, published in 2002 and 2017, respectively. While Bernstein’s third and newest novel, Reckoning: Race War Comes to America, differs from his earlier works of fiction due to its more pessimistic tone, it is, nevertheless, a most welcome addendum to Bernstein’s impressive and ever-growing oeuvre.

Reckoning is set in a near-future dystopian United States. Racial conflicts have escalated to an unprecedented degree, and the US is close to experiencing a racial war that threatens to undermine her fundamental principles, such as individual rights and liberty. On the one hand, the Maccabees, a group of Jewish activists led by Marko Weinhaus, is becoming increasingly aggressive against blacks. Weinhaus succeeds in inciting violence against blacks by arguing in a Hobbesian and Nietzschean fashion that human life is characterized by inevitable conflicts. The core thesis of his book Nature Against Jews, for instance, reads as follows:

Human life, showed the book, was a violent struggle. God’s will was discerned not from revealed texts, which spewed fables, but from history, which dispensed facts. If there were an omnipotent ruler—with a plan—then facts, of both the natural and social orders, not platitudes, expressed it. Knowledge of human history—of ceaseless warfare and blood-drenched extermination—definitively established the nature of God’s world, which manifested a single, concordant, uncontradicted theme: Conquer or be conquered—and the conquered need expect no mercy.1

Given his deterministic stance, Weinhaus urges that “[t]he Jews accede not to man but to nature—or they will be exterminated.”2 While other Jewish activists, such as Jacob Paris, are intent on preventing full-scale race war, Weinhaus holds that there can be no peace between Jews and blacks, whom he considers New Fascists:

Rabbi Paris thinks race war can be averted, that peace between Jews and the black race that spawns the New Nazism can be achieved. … [H]e should know better. The Maccabees are descendants of German Jews who lost their people to the Old World Nazis, and who have not forgotten— who will never forget—that it started with just such rabble in the Munich gutters. Do not, my friends, abandon America to the Nazis. If America falls to the New Nazis, then America’s Jews—the most educated, the most wealthy, the most influential Jews of history—are doomed, and without them, so is Israel.3

On the other hand, a group of black activists, led by Amiri Bantu Biko, shows and expresses increasing hostility against Jews. Like Weinhaus, Biko is convinced that there can be no peace among different races. “If the question is, what drives human history, then race war is the answer,”4 he concludes. According to Biko, it is, for instance, in the nature of whites to dominate blacks. As he explains it:

[T]he white man understands. But he does not care. It’s bloodlust to dominate the dark races that impels him to ghastly brutality. Adam Smith showed slavery unprofitable in contrast to free trade and free labor but the white man pursued it anyway. Why? Because he was not after profit—but dominance to the death over black men, power to rape black women by the thousands, to gestate little half-breed bastards he could further subjugate, and indulge himself with the lash across a million prostrate backs.5

At the core of his novel, Bernstein tragically illustrates how such racial conflicts, if not mitigated, can lead to full-scale race war in less than a week.

Yet despite his excellent graphic illustrations of the brutality of race conflicts, Bernstein is at his best not when actually describing this violence but when revealing its underlying causes. He primarily does so through the portrayal of Dr. Marius Winter, a brilliant(ly perverted) professor who teaches his students about the perennial and supposedly unavoidable conflicts between whites and blacks. “Whites are snow people …,” Winter argues, “[t]hey are of the glacial north, frigid, Aryan, glorifying the Vikings from whom they descend. They are unlike us—heat people—bursting with warmth, flooded with African sun from our birthplace.”6 At a superficial glance, Winter seems to acknowledge that whites have improved their behavior toward blacks. As he tells his students, “The white man, today … he reads black writers, he hires black professors, he votes for black candidates, he supports a black mayor.”7 This alleged improvement, he explains to them, is merely a masquerade, though. Far from attempting to peacefully coexist with blacks, whites, Winter holds, are merely waiting for the right moment to annihilate them:

The white man is patient. He waits out the ebb and flow of history. He retreats when prudent. He gives up his colonies when indigenous peoples rise. But he controls the world’s wealth. He speaks of social welfare and doles out scraps to the dark races. He smiles. He gets them off guard. His business and military agents are everywhere. His intelligence officers preside over a worldwide machine. He awaits the propitious moment. Like a poisonous reptile, he replenishes venom during peacetime lull. The snow people with ice water for blood and a calculator inside their skulls await the opportune moment.8

Winter finishes this particular class by asking his students, “Has there ever been a dark revolution that overthrew the white race in any of its northern homeland nations and established the black man’s rule?” When a student replies, “No!,” Winter comments, “Wrong answer. … Not yet,” intent on turning his brainwashed students into violent activists.9

Bernstein further proves his thorough understanding of the historical role the intelligentsia has played in revolutions when showing that it is not only Winter’s students but also Winter himself who is ultimately nothing but cannon fodder in the forthcoming Black Revolution. When Winter asks Biko for a bodyguard, the latter tells his right hand Alonzo, “Dr. Winter desires a bodyguard. … Under no circumstances do you find him a bodyguard. Never—do you hear me?”10 And, thus, “[t]he brilliant educator, Marius Winter, who had devoted his life to the cause [is about to become] the first martyr of the Black Revolution.”11 Unlike Winter who allegedly longs for merely an intellectual revolution, Biko understands that Winter’s theories will have practical consequences. Reflecting on this issue, Biko concludes, “Winter, he knew, preferred his revolution in the classroom, in books and cozy libraries, in theory. He shook his head, staring at the soon-to-be-filled arena. But revolutions only began in the mind. They finished in the street.”12

Bernstein’s universe is not a simplistic one of two antagonistic and deterministic groups, though. Other characters in the novel are intent on averting full-scale race war in sometimes questionable ways. New York’s Mayor Teddy Buckley, for instance, intends to mitigate the upcoming eruption of violence by means of violence. According to him, “the most brutal law-and-order mayor in New York City’s history,”13 force can never be tolerated but must always be brutally counteracted by government measures. Dr. Benedict Stonebreaker, in contrast, holds that racial peace can be achieved—yet only by means of segregation: “The solution he preached should be obvious to all but was apparent to none. Do not exterminate contrasting races but segregate them.”14

Other characters develop more fruitful approaches to averting the upcoming catastrophe, however. Reverend James Christian Steele, “a tireless campaigner against anti-Semitism, anti-black racism, and bigotry of all forms,”15 for instance, understands that both Weinhaus’ and Biko’s deterministic ideas are unsound. “Weinhaus, Biko, their toadies,” he concludes, “projected their own demonic version of simplicity.”16 In contrast to other characters in the novel, Steele is convinced that different races can exist in harmony without being segregated. Bernstein illustrates Steele’s optimistic stance in an emotional and beautifully written scene:

“Reverend Steele, is that you?” [a male figure] asked. He was a black man, middle-aged, slightly taller than Steele, broad, like the minister, through the shoulders and chest. He wore a work-grimed uniform with the words Griffin Auto Body stitched across its left chest. He extended his hand.

Steele took it. The man clung to it in a powerful grip.

“I’m with you,” he said. “Many of my customers are Jews. Put a stop to this madness.”17

Yet the novel’s greatest hero is perhaps Antony. Like Steele, Antony takes a firm stance against violence: “Killing, he well knew, was a cancer in a man’s soul. Too easily it could metastasize. Including the killing of monsters in a righteous cause.”18 Unlike the radical activists on both the Jewish and the black side who are oblivious to the bloodshed their actions are about to incur, Antony is painstakingly aware of the horrors of full-scale race war: “Race war. Human bodies hacked to fragments by machetes, body parts stacked in piles like so much cordwood—children, babies, adults cleaved to segments, as though calves in a slaughterhouse.”19

In contrast to Steele, who mainly tries to avert the catastrophe by conversations, though, Antony is a man of action. Despite not knowing whether or not his actions can ultimately prevent full-scale race war, he courageously attempts to take a stance by publicly exposing Biko’s and Winter’s ideas in front of their audience: “Could race war in Brooklyn be averted? He [did] not know [it]. But could Biko, Winter, and the bodyguards be exposed before their panting admirers as the vicious racists they were? Vigorously, he nodded. Yes, they could.”20 Unlike the radical activists who focus on differences and conclude that races are in perpetual conflict, Antony is interested in similarities and reasons that people from different races can peacefully coexist. “The Jews,” he bravely announces in front of a radicalized black audience, “are the most persecuted minority of European history … They are not the black man’s enemy—but his exemplar.”21 Celebrating Albert Einstein as “the most accurate modern representative of the Jew,”22 Antony highlights that great achievements can be accomplished by any thinking individual, regardless of one’s race.

Through the character of Antony, Bernstein shows us that consistently championing individual rights is the one and only solution to avoid race war. Yet, ultimately, it is Rabbi Jacob Paris who eloquently expresses this stance in Reckoning. “Every individual,” Paris explains early in the novel, “is unique and unrepeatable. There’s only one race that matters: the human race.”23 Segregation, he teaches, will not make us flourish. Rather, this policy effectively prevents us from interacting with moral people from any race other than our own. As he puts it, “We impoverish our lives—we don’t merely segregate the oppressed group from us, in so doing we segregate ourselves from them, from the best among them—from the geniuses and the saints and the psychologists and the humanitarians.”24

Bernstein exemplifies peaceful, interracial relationships by Jacob Paris and James Steele’s friendship. Describing them, he writes, “They talked, encouraged, exhorted, they set an example, two men of differing races but identical, for what was the color of peace? They turned out of a narrow lane onto a broad boulevard.”25 Even more prominent and touching, though, is Bernstein’s retrospective description of the romantic relationship between Jewish Nazi hunter Mick Davidson and his deceased Arabic wife Fatima:

Mick Davidson had not had a love affair in more than six years. Not since his wife had been murdered. Fatima, the shining one, he thought, an Arab, more of an observant Muslim than he was a Jew, a nurse, loyal to Israel, an informant of Israeli Intelligence whose covert information had foiled at least one terrorist attack. There had been opportunities. But Fatima’s graceful, dark-haired form was ever with him.26

Despite the fact that Fatima was brutally murdered by a group of five Palestinian terrorists, Mick knows that this horrific act was perpetrated not by five members of a certain race but by five perverted individuals. Hence, he does not feel hatred for each and every Palestinian but rather thinks about all those individuals who peacefully coexist with people from other races: “The who and the what, he thought. What were they, the five Palestinian terrorists who had tortured Fatima to death and then shipped body parts to Mossad headquarters? Her family and many Israeli Arabs lived peacefully with Jews.”27

Yet how can we actually create a nation of “color blind individualism”28 to avert full-scale race war? The solution, Bernstein argues, is not government interference but education. To illustrate a rational approach to education,29 Bernstein incorporates the passionate story of Jessica Collins into his novel:

Jessica Collins … had quit the local public school in exasperation, convinced that ghetto kids could vastly exceed the limited academic expectations stipulated by governmental bureaucracy … [She] had long known that reading was the key—that love of reading was the key. She rescued a set of phonics texts from the trash bin of the local public school, she set up in her tiny Brooklyn apartment her own school, she charged whatever local families could afford, she admitted all students, regardless age, gender, race, or history. She accumulated a library, stories of adventure, of impassioned love, of poor persons rising, of black champions, of Asian champions, of white champions, of brilliant, plucky young female detectives, of great plots, towering heroes, and of daunting impediments overcome. She read the stories to her kids, until she saw in their wide eyes recognition of the treasures embodied in books, until they demanded, not requested, to read the precious books themselves. Then she taught them to read.30

Unlike modern educators who claim that the US is inherently racist,31 Jessica Collins teaches her students that there are heroes in every race and that they need to be celebrated for their achievements. Thus, genuinely admiring humans at their highest potential, regardless of their race, Bernstein holds, is the key for overcoming racial conflicts and averting full-scale race war.

In toto, Bernstein’s Reckoning is a tour de force. In this novel, Bernstein, once again, proves that he is a polymath sui generis. Throughout the book, he continuously showcases a superb understanding of philosophy, theology, politics, and history, American and German, Jewish and black, alike. More importantly, though, Bernstein’s message is not nihilistic. Instead of merely deploring the fact that the US has become increasingly racially divided, Bernstein both reveals the reasons behind this trend and offers a profound antidote to this central present-day problem.

Yet, at the same time, it can hardly be denied that the overall tone of the novel is gloomy. After all, Reckoning is set in a dystopian nightmare universe and Bernstein graphically details scenes full of brutality, conflict, and violence. Thus, you may wonder why you should read Bernstein’s newest book rather than a Romantic classic by, say, Victor Hugo.

The reason is to prevent Bernstein’s dystopia from coming true. In addition to immersing yourself in a thrilling plot, you are presented with powerful philosophical ideas to combat racism. Since humans have free will, full-scale race war can still be prevented if people change their ideas. Hence, if you want to learn how to fight for a more peaceful future both for yourself and for your children and grandchildren, this is the book for you.

Throughout its history, the internal stability of the US has been threatened by many issues, ranging from slavery through the New Deal reform programs to environmentalist activism. Racial conflicts are yet another problem which the US has to cope with. However, as with all other problems, this issue can be overcome by the right philosophical ideas. Thus, even if Bernstein’s message seems at times gloomy, it might be noteworthy to remember the optimistic message of Reckoning. Its theme is colorblind individualism versus racism in any form—and the former does triumph.

Andrew Bernstein, Reckoning: Race War Comes to America (New York: Hybrid Global, 2023), 34.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 36 [emphasis in the original]).

Bernstein, Reckoning, 24.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 87 [statement italicized in the original].

Bernstein, Reckoning, 55.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 16.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 18.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 19.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 19.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 61.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 61.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 82.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 12.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 39.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 2.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 42.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 43.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 87.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 88.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 92.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 132.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 128.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 3.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 50.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 110.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 4.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 100.

Bernstein, Reckoning, 115.

For more on this issue, cf. Andrew Bernstein, Why Johnny Still Can’t Read or Write or Understand Math: And What We Can Do About It (New York: Bombardier, 2022).

Bernstein, Reckoning, 182 [emphasis in the original].

For more on this issue, cf. Andrew Bernstein, “The Case for Western Civilization,” The Objective Standard 19.3 (2024), 11-38.