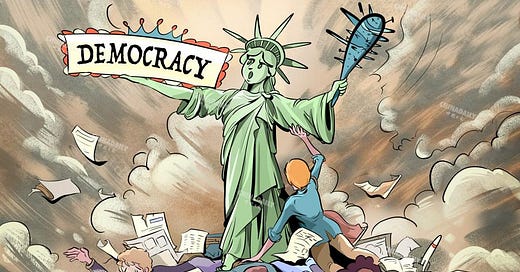

In last week’s short, I discussed the differences between a democracy and a republic, arguing that the United States of America is not a democracy but a republic while also giving indications why the US could not have survived as a nation if she had been founded as a democracy rather than as a republic. While doing so, I pointed out that myriad politicians from both major parties have repeatedly made the claim that the US is a democracy. One of the examples I used in this discourse was former President George W. Bush, who justified post-9/11 interventions in the Middle East by arguing that the allegedly democratic US should be committed to making Asian nations more democratic.

After posting my short, one of my students reached out to me, asking me to further elaborate on my views on US foreign policy. In his response to my post, he correctly emphasized my aversion to Bush’s idea that the promotion of democracy was a valid justification for the invasion of other nations. However, my student wondered about my views about whether or not the US is justified to intervene in the affairs of other nations in order to internationally promote constitutional republicanism or “Americanism” (rather than democracy). It is this excellent question I would like to analyze in this week’s short.

First and foremost, it is important to point out that the United States does not have a duty to play the world police and self-sacrificially ensure global peace. Rather, the US should only engage in international affairs if it is in her own self-interest to do so. As Ayn Rand puts it, “When a nation resorts to war, it has some purpose, rightly or wrongly, something to fight for—and the only justifiable purpose is self-defense.”1 In other words, it is the responsibility of the US government to protect its citizens whenever another nation poses a serious threat to national security.

Whether or not the US should enter an international conflict to liberate a dictatorship which does not pose a threat to national security or to defend a (semi-)free country from being invaded by an authoritarian regime is highly contextual, however. An authoritarian regime, i.e. a nation which enslaves its own citizens, can hardly claim that it safeguards the rights of its own citizens. Consequently, the US has the right (though not the duty) to overthrow dictatorial regimes or to defend her (semi-)free allies from dictatorial enslavement. In Rand’s words:

Dictatorship nations are outlaws. Any free nation had the right to invade Nazi Germany and, today, has the right to invade Soviet Russia, Cuba or any other slave pen. Whether a free nation chooses to do so or not is a matter of its own self-interest, not of respect for the nonexistent ‘rights’ of gang rulers. It is not a free nation’s duty to liberate other nations at the price of self-sacrifice, but a free nation has the right to do it, when and if it so chooses.2

The fact that the US has the right to invade another dictatorship does not imply that any nation has the right to invade any other nation, though. Rather, only a country that upholds individual rights has the right to invade a country that does not protect the rights of its citizens. China, for instance, does not have the right to invade North Korea in order to substitute one form of communism for another variant of communism. Nor does Venezuela have the right to invade Cuba in order to substitute socialism for communism. As the freest nation on earth, the US, in marked contrast, has the right to invade a dictatorship or defend its allies from dictatorial rule when and if she intends to liberate a dictatorship or protect a semi-free country, i.e. when and if she intends to promote constitutional republicanism or “Americanism,” as my student puts it. As Rand remarks:

Th[e] right [to invade dictatorship nations] … is conditional. Just as the suppression of crimes does not give a policeman the right to engage in criminal activities, so the invasion and destruction of a dictatorship does not give the invader the right to establish another variant of a slave society in the conquered country.

A slave country has no national rights, but the individual rights of its citizens remain valid, even if unrecognized, and the conqueror has no right to violate them. Therefore, the invasion of an enslaved country is morally justified only when and if the conquerors establish a free social system, that is, a system based on the recognition of individual rights.3

These observations explain why neither the US nor any other country has the right to invade a collectivist country in order to spread democracy. As pointed out in last week’s short, democracy literally means mob rule. A democracy is a social system under which the citizens can expropriate (or even murder) their fellow citizens by means of simple majority vote. Thus, democratic rule is nothing but another variant of collectivism which does not safeguard but violates individual rights. Leonard Peikoff reminds us of this fact when stressing, “‘Democracy’ means a system of unlimited majority rule; ‘unlimited’ means unrestricted by individual rights. Such an approach is not a form of freedom, but of collectivism.”4

Thus, a democratic country does not have a moral right to invade another collectivist nation merely to substitute one variant of collectivism for another. As so often, though, morality goes hand in hand with practicality. Invading another nation to democratize it is not only immoral but also impractical.

Imagine, for instance, that a democratic country resolves to invade a communist regime in order to liberate its citizens. Even if the former nation succeeds in overthrowing the latter’s tyrannical dictator, the odds of establishing a free system in the conquered country are extremely low. After all, revolutions are not, as Marx claimed, primarily political but primarily epistemological. Political change presupposes educational change. Indoctrinated by propaganda for decades, the citizens of the communist nation are likely to vote for communism again after acquiring the right to vote. Rand exemplifies this problem when discussing US involvement in the Vietnam War, highlighting, “They tell us that we must defend South Vietnam’s right to hold a ‘democratic’ election, and to vote itself into communism, if it wishes, provided it does so by vote—which means that we are not fighting for any political ideal or any principle of justice, but only for unlimited majority rule, and that the goal for which American soldiers are dying is to be determined by somebody else’s vote.”5

A constitutional republic, in marked contrast, has not only the right but even the obligation to defend its citizens if another nation threatens their liberty and warfare. The reason is that the only proper function of the government is to protect individual rights. A proper, moral government does so by providing three services, namely the police, a voluntary army, and courts based on objective law. “The proper functions of a government,” Rand explains, “fall into three broad categories, all of them involving the issues of physical force and the protection of men’s rights: the police, to protect men from criminals—the armed services, to protect men from foreign invaders—the law courts, to settle disputes among men according to objective laws.”6 Since a free nation is obliged to defend its citizens from foreign invaders, there can be no doubt that the US has both a right and an obligation to defend itself if attacked. “[W]hen a foreign country initiates the use of armed force against us,” Rand points out, “it is our moral obligation to answer by force—as promptly and unequivocally as is necessary to make it clear that the matter is nonnegotiable.”7

Whether or not the US should also engage in international affairs for reasons other than self-defense is a much more intricate and contextual issue, though. What ultimately matters to make a decision about whether or not to engage in an international conflict is her (long-term) self-interest. As previously mentioned, the US should not engage in a war if her only justification is the fruitless hope to self-sacrificially help another nation (e.g. by making it more democratic). In other cases, though, the US might have good reasons to become involved in international affairs. What is important, I think, is that politicians have a clear idea of why the US should enter a conflict, what her soldiers are fighting for, and how the conflict can be ended as quickly and efficiently as possible. Given a firm ideological basis and a strategic plan, the US could help solve many international conflicts while at the same time advancing her self-interest. After all, creating constitutional republics with free markets around the globe would result in a more peaceful world, an increase in trade partners, and, consequently, a reduction in production costs. “The essence of capitalism’s foreign policy,” Rand reminds us, “is free trade—i.e., the abolition of trade barriers, of protective tariffs, of special privileges—the opening of the world’s trade routes to free international exchange and competition among the private citizens of all countries dealing directly with one another.”8

Unfortunately, when it comes to addressing and solving international affairs, the United States has been without a firm ideological basis or a strategic plan for decades. Rather than consistently defending her (semi-)free allies and crushing dictatorial regimes, the US has become highly pragmatic when engaging in international conflicts. Ultimately, her middle-of-the-road approach has not made the world a freer place but actually prolonged conflicts around the globe. But this is a topic for another day.

Ayn Rand, “The Wreckage of the Consensus,” Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, 2nd ed (New York: Signet, [1966] 1967), 253.

Ayn Rand, “Collectivized ‘Rights,’” The Virtue of Selfishness: A New Concept of Egoism (New York: Signet, [1964] 2014), 122 [emphasis in the original].

Rand, “Collectivized ‘Rights,’” 122 [emphasis in the original].

Leonard Peikoff, Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand (New York: Meridian, [1991] 1993), 368.

Rand, “The Wreckage of the Consensus,” 253-254. Two other crucial examples are the First and the Second World War. The US entered both these wars to democratize nations abroad yet (involuntarily) ended up helping create collectivist dictatorships. Cf. Ayn Rand, “The Roots of War,” Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, 38: “Just as Wilson, a ‘liberal’ reformer, led the United States into World War I, ‘to make the world safe for democracy’—so Franklin D. Roosevelt, another ‘liberal’ reformer, led it into World War II, in the name of the ‘Four Freedoms.’ In both cases, the ‘conservatives’—and the big-business interests—were overwhelmingly opposed to war but were silenced. In the case of World War II, they were smeared as ‘isolationists,’ ‘reactionaries,’ and ‘America-First’ers.’ World War I led, not to ‘democracy,’ but to the creation of three dictatorships: Soviet Russia, Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany. World War II led, not to ‘Four Freedoms,’ but to the surrender of one-third of the world’s population into communist slavery.”

Ayn Rand, “The Nature of Government,” The Virtue of Selfishness, 131 [emphasis in the original].

Ayn Rand, “The Lessons of Vietnam,” The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought (New York: Meridian, 1990), 145.

Rand, “The Roots of War,” 35 [emphasis in the original].

Re US foreign policy: have you come across the Powell Doctrine? Gen. Colin Powell served in the debacle that was the Vietnam War and was an advisor to POTUS Bush in 1990, when the Gulf War was being considered. With Vietnam in mind, Powell formulated a series of questions that must answered affirmatively before the US commits to military intervention. The questions are summarized at

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-powell-doctrines-wisdom-must-live-on/

Here they are:

1. Is a vital national-security interest threatened?

2. Do we have a clear and attainable objective?

3. Have the risks and costs been fully and frankly analyzed?

4. Have all other nonviolent policy means been fully exhausted?

5. Is there a plausible exit strategy to avoid endless entanglement?

6. Have the consequences of US action been fully considered?

7. Is the action supported by the American people?

8. Do we have genuine broad international support?

There's a lot of room for debate about what a national-security interest is, and I don't agree that we necessarily need broad international support, but I wish our involvements abroad were consistently based on these!

I came across the Powell Doctrine while researching my Timeline 1900-2021. Unfortunately, I'm not sure anyone except POTUS Bush ever applied it.